INTRODUCTION

When the opposition between the Western and Soviet blocs ended, revealing a possible 'end of history', 3 ( * ) the 1990s saw the rise of liberal democracy and the market as vectors of growth, trade and peace that would lead to a drop in world conflicts. But the 21 st century opened a new era of uncertainty.

The beginning of this century has been characterised by the emergence of new dangers - in particular risks from jihadists as well as cyber and a whole range of new so-called "hybrid" threats - by the new assertiveness of powers with destabilising aims - Russia, Turkey and Iran, to focus on the recent period and our immediate environment - and by America's world leadership that is gradually being challenged by the spectacular rise of China. Obsessed with its Asian competitor, the Obama administration began a "pivot to Asia" in 2011 which, in the long run, called into question the priority NATO gives to Europe's security.

It is true that, since the 1990s, the European Union had gradually established a common security and defence policy (CSDP). But its ambitions were limited. Most Member States, either because they felt they faced too great a threat, particularly on the eastern edge, because their defence capabilities were too weak, or both, essentially continued to rely on NATO's security guarantee to the Allies. This guarantee, which is primarily provided by the Americans, whose colossal military expenditure - by far the largest in the world - represents 70% of all Allied spending, was deemed immeasurably more reassuring, convenient and, in short, economical.

Due to an awareness of the scissor effect resulting from an increased number of threats--not all of which fall within NATO's remit--and the risk of a security guarantee within the Alliance that is less unconditional from the Americans, European Union Member States have recently been encouraged to do more for their security.

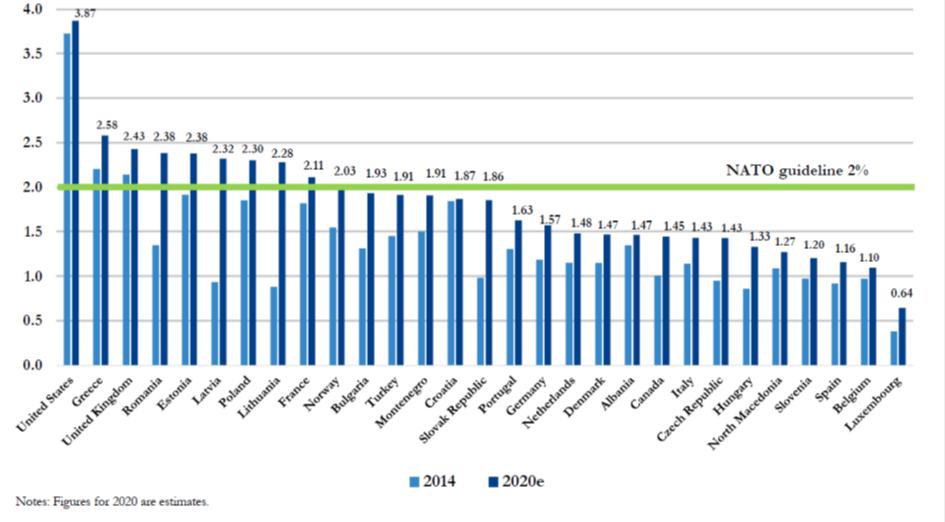

The Americans themselves are directly calling for better 'burden sharing' on defence between Allies, so much so that each of them agreed to spend 2% of their GDP on defence within 10 years at the NATO summit in Newport in 2014. This resulted in a reversal of the downward trend in defence spending among EU countries from 2015.

DEFENCE SPENDING AS A SHARE OF GDP IN 2014 AND IN 2020 (%) 4 ( * )

%

The Trump administration openly called into question America's guarantee of transatlantic coverage. Once the shock had passed, Europeans increasingly asked themselves if the time was right to effectively jumpstart the CSDP to prepare for any eventuality.

This would be no mean feat for a policy that is often criticised for its complexity, illegibility and even relative ineffectiveness (in the sense of added value compared to national initiatives, even combined), and for the indifference of European citizens towards it.

Ultimately, the Biden administration strongly reaffirmed the US commitment to NATO. The European desire for genuine autonomy in security and defence matters could be jeopardised as soon as it was strengthened.

However, the threats outside the Alliance's traditional remit remain. Furthermore, Trumpism is not dead; there is no reason to expect that it will not continue to prosper and offer an electoral proposal that will convince a majority of Americans, if not for the upcoming midterms, then the next presidential elections.

What would happen to NATO's protection if it had to weather four more years of US suspicion towards their European allies? Four years of an American foreign policy that relies on challenging multilateralism? Four years of uninhibited middle powers, using a range of new conflict powers, feeling freer than ever to engage in all sorts of actions in order to unite domestic opinion put to the test by economic difficulties and attacks on freedom?

Today, the European Union is far from able, or even wanting, to take on the role of the world's pole of stability, which would combine a respect for multilateralism and human rights with the universal respect that a leading-rank power inspires. The success of the Biden administration on the domestic front is therefore crucial, since it could determine the political sustainability of the return of the United States to the world stage, which Europeans are now seeing with relief, and the advent of a new Pax Americana - whether under the UN or NATO banner.

Still influenced by the sudden American dawn, the Europeans are betting on this favourable scenario, assuming that, even today, European defence--in the sense of a defence of European territory--as envisaged by the Treaty of Amsterdam (see below) can only be foreseen in the distant future.

However, even in this optimistic scenario, some Allies--such as the United States, the United Kingdom or Turkey--might not want to follow the EU in a crisis management operation outside its territory, which the EU would nonetheless deem indispensable for its security. Let's remember the Obama administration's decision not to intervene in Syria in 2013. The US does not want to engage directly in the Sahel either for the moment. The increase in the risks in a more unstable, unpredictable world, a harbinger of a possible return to demanding, so-called 'high intensity' operations in external theatres that interest the European Union far more than NATO, is a shared observation. However, given its current desire, capabilities and organisation of its security and defence, everything leads us to believe that the European Union would struggle to establish an effective, proportionate intervention force.

Can the European Union give itself the resources to take on this minimal crisis management role, in supplement to the role that NATO plays for its territorial defence? It has been trying for thirty years, more or less.

Here, it is not useful 5 ( * ) to go back to the project for a European Defence Community (EDC) that France rejected in 1954 or the Western European Union (WEU) set up the same year. 6 ( * ) In the contemporary international order, the shared acknowledgement of the need for an effective European security and defence apparatus goes back to the wars in Yugoslavia (1991-2001), which, with some 150,000 deaths in 10 years, offered the distressing spectacle of a Europe incapable of acting on its own doorstep without turning to NATO, i.e. the United States.

The Maastricht Treaty, which came into force in 1993, introduced the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) as the second pillar of the EU. In 1997, the Treaty of Amsterdam gave the CFSP the task of ' the progressive framing of a common defence policy, which might lead to a common defence ', with the goal of being able to carry out the Petersberg tasks. 7 ( * )

At the Franco-British summit in Saint-Malo in 1998, the United Kingdom lifted its veto on the creation of European crisis management capabilities. In 2003, the first EU missions and operations took place .

Then, in 2004, the Treaty of Nice specifically established the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP), which was succeeded by the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) , an integral part of the CFSP, in the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009. The position of High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HR/VP) was created. They have authority over the European External Action Service (EEAS), established in 2011, which manages the EU's diplomatic relations with non-member countries and conducts the CFSP. Since 2016, special attention has been paid to CSDP instruments with a new flurry of initiatives of varying outcomes, bearing in mind that CFSP/CSDP decisions are still adopted in principle by unanimity.

Of course, a defence and security policy cannot be conceived without a strategic document, and so in December 2003 the " European Security Strategy " was adopted, which even then was based on a common threat assessment and defined objectives to promote the European Union's security interests. It was revised in 2007 and succeeded by the "European Union Global Strategy" (EUGS), adopted on 28 June 2016, which is now the EU's updated doctrine for improving the effectiveness of the defence and security of the Union and its Member States. 8 ( * )

All in all, the record of thirty years of summits, meetings, votes, treaties, plans, establishment of bodies and instruments of all kinds to strengthen and organise the security and defence of the EU remains disappointing. Thirty years of effort have not produced a detailed and shared diagnosis of the threats facing the EU, forces that can be immediately mobilised to respond to a crisis, effective decision-making procedures for launching an operation, nor a capability process that provides sufficient incentives to make up for the EU's shortcomings in terms of the availability and production of the necessary equipment. Despite some promising advances, it has largely been thirty years of posturing.

However, there is now a general agreement that Europe needs to do more in the field of security and defence in the face of the growing scope and variety of threats. But experience shows that divergences never fail to appear whenever the time comes for specificity on the issues that generally require unanimity.

So, the time seemed right to tackle once again all the outstanding problems while looking for an approach that was new in both its method and breadth of vision.

This is the spirit in which Germany proposed in 2019 the drafting of a 'strategic compass', which would be a sort of white paper on the EU's security and defence.

Launched under the German Presidency of the Council of the EU in the second half of 2020 and expected to be finished during the French presidency in the first half of 2022, this exercise organises a reciprocal exchange between experts and representatives of all Member States on an unprecedented scale.

It starts with an assessment of the threats on all fronts , from conventional conflicts to supply shortages--a risk highlighted by the health crisis--to attempts to deny access to certain spaces, misinformation, and computer hacking. To identify the measures to take as a result of these threats, the approach widens its focus : beyond the traditional areas of crisis management and the civilian and military capabilities that this requires, it is structured to deal equally with resilience , favouring a more comprehensive response to the variety of threats, and with partnerships , including NATO. Indeed, it seemed necessary to tackle these four chapters together in order to promote the emergence of a truly geopolitical European Union, strong and free to decide its own destiny, which could exist on the geopolitical stage.

What phase have we reached in the process of this strategic compass, which indeed seems decisive for the future of Europe and our collective security? What hopes can this approach reasonably raise? Does it not entail certain risks --particularly in the light of recent international developments-- and how can we guard against them, where appropriate?

Looking for answers means tackling complex issues that are either dealt with in a piecemeal and technical manner by experts speaking to other experts, or in a more political way but which is based on arguments of authority. Sometimes--and this is typical of French leaders--these issues give rise to clear analyses that lead to strong proposals, but which disregard the range of sensitivities that exist among European partners. There is a risk that these proposals will be received, with an often-perceptible annoyance, as pro domo pleas to reinforce an autonomy that matches the French vision of these issues, but which is in reality unrealistic, even dangerous.

This is the purpose of this report is to provide reasoned answers to these essential questions , placing them in their context so that they can be understood by Europe's citizens, whose future is at stake.

Shedding light in this way on the terms of the debate could strengthen the ambitions of the Strategic Compass for the benefit of a common good: a Europe that is free yet respectful of its commitments, a Europe that is strong yet aware of its limits, a Europe that is both prosperous and protective.

*

To gather input for their work, the rapporteurs held hearings with French and European administrations, experts, members of the European Parliament and officials in the defence ministries of other EU Member States (list in the annex). They also sent a questionnaire (also in the annex) on the Strategic Compass to all French embassies in EU countries.

* 3 'The End of History and the Last Man', Francis Fukuyama, 1992.

* 4 Based on 2015 prices and exchange rates. Estimate for 2020. Source: NATO, 'Defence spending of NATO countries (2013-2020)', October 2020.

* 5 It provided for a European army under the supervision of the NATO Commander-in-Chief, who was appointed by the US President.

* 6 The WEU was dissolved in 2011 and incorporated into the European Union.

* 7 Defined in 1992 within the framework of the Western European Union (WEU), the so-called 'Petersberg tasks' include humanitarian or rescue tasks, peacekeeping tasks, and combat forces for crisis management (including peace-making operations). They effectively sought to ward off the risk of repeating the humiliation of Yugoslavia.

* 8 The EUGS articulates the EU's foreign policy actions in five main areas: the security of the Union, governmental and societal resilience in neighbours to the east and south, an integrated approach to conflict, regional orders of cooperation, global governance in the 21st century. In the field of security and defence, the EUGS lays out three strategic priorities: react to foreign crises and conflicts, reinforce capabilities in partner countries, and protect the Union and its citizens (see box below).