Rapport d'information n° 753 (2020-2021) de M. Ronan LE GLEUT et Mme Hélène CONWAY-MOURET , fait au nom de la commission des affaires étrangères, de la défense et des forces armées, déposé le 7 juillet 2021

Disponible au format PDF (956 Koctets)

-

SUMMARY

-

INTRODUCTION

-

A GENERAL PRESENTATION OF THE STRATEGIC

COMPASS

-

I. A COMPASS FOR A FREE, STRONG AND PROTECTIVE

EUROPE

-

A. RECONCILING ASSESSMENTS...

-

B. ... TO JUMPSTART THE CSDP ...

-

1. The capability aspect

-

a) Overcoming inertia

-

b) Instruments to be mobilised...

-

(1) The European Defence Agency (EDA)

-

(2) The Capability Development Plan (CDP)

-

(3) The Coordinated Annual Review on Defence

(CARD)

-

(4) Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO)

-

(5) The European Defence Fund (EDF)

-

c) ...and to better interact, including with the

operational aspect

-

(1) A necessary coordination

-

(2) Looking for an overall coherence with the EU's

level of ambition

-

a) Overcoming inertia

-

2. The operational aspect

-

a) A desire that needs a jumpstart

-

b) Overcoming the principle of unanimity

-

(1) The current easy way to take quick action or

overcome opposition is ad hoc coordination.

-

(2) The possibility for automaticity in case of

aggression

-

(3) The avenue of facilitated consent

-

(4) The avenue of bypassing institutions: EII and

other initiatives

-

(5) The avenue of a hard core: a European Security

Council?

-

c) Improvements within easy reach

-

(1) Improve mission quality

-

(2) Accelerating force generation: finally a

legacy for EU BGs?

-

(3) Better funding for missions: the European

Peace Facility (EPF)

-

(4) Europeanise military command

-

(i) The first steps towards a European command

with the Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC)

-

(ii) The methods for a balanced increase in

power

-

(5) Provide information to military command

-

d) Establish a more broadly helpful cluster

dedicated to defence?

-

a) A desire that needs a jumpstart

-

1. The capability aspect

-

C. ... AND RESIZING THE EU'S ACTIONS TO MEET ITS

SECURITY NEEDS

-

A. RECONCILING ASSESSMENTS...

-

II. A COMPASS THAT MIGHT POINT A LITTLE TOO FAR

WEST

-

III. A STRATEGIC COMPASS THAT HAS BECOME

RISKY

-

I. A COMPASS FOR A FREE, STRONG AND PROTECTIVE

EUROPE

-

CONCLUSION

-

COMMITTEE EXAMINATION

-

LIST OF EXPERTS CONSULTED

-

QUESTIONNAIRE SENT TO EMBASSIES

N° 753

SENATE

EXTRAORDINAIRY SESSION OF 2020-2021

Filed at the President's Office of the Senate on 7 July 2021

INFORMATION REPORT

DRAWN UP

on behalf of the Foreign Affairs, Defence and Armed Forces Committee (1) on « What Strategic Compass for the European Union ? »,

By Mr Ronan LE GLEUT and Mrs Hélène CONWAY-MOURET,

Senators

(1) This committee is composed of : Mr Christian Cambon , Chairman ; Messrs Pascal Allizard, Olivier Cadic, Olivier Cigolotti, Robert del Picchia, André Gattolin, Guillaume Gontard, Jean-Noël Guérini, Joël Guerriau, Pierre Laurent, Cédric Perrin, Gilbert Roger, Jean-Marc Todeschini , Deputy Chairpersons ; Mss Hélène Conway-Mouret, Joëlle Garriaud-Maylam, Messrs Philippe Paul, Hugues Saury , Secretaries ; Messrs François Bonneau, Gilbert Bouchet, Ms Marie-Arlette Carlotti, Messrs Alain Cazabonne, Pierre Charon, Édouard Courtial, Yves Détraigne, Ms Nicole Duranton, Messrs Philippe Folliot, Bernard Fournier, Ms Sylvie Goy-Chavent, Mr Jean-Pierre Grand, Ms Michelle Gréaume, Messrs. André Guiol, Alain Houpert, Ms Gisèle Jourda, Messrs Alain Joyandet, Jean-Louis Lagourgue, Ronan Le Gleut, Jacques Le Nay, Ms Vivette Lopez, Messrs Jean-Jacques Panunzi, François Patriat, Gérard Poadja, Ms Isabelle Raimond-Pavero, Messrs Stéphane Ravier, Bruno Sido, Rachid Temal, Mickaël Vallet, André Vallini, Yannick Vaugrenard, Richard Yung .

SUMMARY

|

KEY OBSERVATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ? Europe's citizens know almost nothing about the discussions under way about the Strategic Compass , the European Union's upcoming strategic document for 2030 that will structure its security to a considerable extent. The national representative bodies that are the Member States' parliaments have been excluded from this process , even though it will have a significant impact on the future. This report tries to correct this oversight by informing the public , because the subject is complex, and by alerting them, because the risks and stakes are high. In the future, parliaments must be involved in periodically updates on the Strategic Compass . ? The work on the Compass has been limited to experts and the executive branches and was launched during the uncertain period inaugurated by the Trump administration , which questioned the security guarantee that NATO provides to Europe. The Biden Administration has reassured the Allies and reaffirmed NATO's coverage, so much so that their ambitions for Europe's security and defence have been greatly scaled back. ? However, Trumpism is not dead , and even if it does die, the United States' strategic interests do not always coincide with those of the EU, so it should take care to leave room for manoeuvre and autonomy in defence and security to manage crises . Furthermore, NATO's responsibilities now tend to cover resilience , a domain that the EU has also taken up via the Strategic Compass. The EU should assert its own priorities whilst seeking coordination with NATO. ? The Strategic Compass should be finalised in March 2022 under the French Presidency of the Council of the European Union (first half of 2022). France is active on issues of defence and security . It readily takes strong initiatives and invokes general principles such as strategic autonomy. The gap between its ambitions and those of most Member States has become obvious . ? If France wants to be convincing, it must take care to listen to its partners and promote balanced measures tactfully and with conviction, especially when working with Atlanticist Member States that are more reluctant than ever to move further towards strategic autonomy. These measures could: - seek to improve how the many instruments intended to overcome the EU's capability shortfalls operate and interact and work to acquire a European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB) by encouraging cooperation, - try to better accommodate the principle of unanimity , which is a major obstacle to initiating operations, which are increasingly rare despite an increase in risks and conflicts, - work to improve operations, in particular by Europeanising military command and speeding up force generation . A 'first entry force' of 5,000 trained troops could be established, finally mobilising the battlegroups; created in 2006, they have never been deployed and are often unavailable. These possibilities would show substantial progress towards a defence and security policy that seems out of steam despite several revivals. France must therefore support the implementation of a mechanism to politically monitor and support the Strategic Compass . ? It may be difficult to walk this fine line, but it is essential, as the potential pitfalls of the Strategic Compass are serious : it could prove to be completely lacking in scope, or it could emerge with ambitions that entirely overlap with those of NATO. Depending on how detailed it is, the Compass could end up being a straitjacket if there is a major crisis . |

|

Recommendations for the French Presidency of the Council of the EU 1. Reiterate that, through the Strategic Compass, the European Union is entitled to set its own priorities, which may be distinct from those of NATO. 2. Take care to support measures (see above) that will appear to our partners as balanced and concrete and support an open and respectful discussion. 3. Promote a mechanism for politically monitoring and supporting the Strategic Compass. 4. Propose that the Strategic Compass be updated every five years, each time involving Member States' parliaments. |

I. A STRATEGIC COMPASS FOR A FREE AND STRONG EUROPE

The start of this century has been characterised by the emergence of new types of threats--jihadist, cyber, spatial, 'hybrid'--destabilising initiatives from middle-ranking powers such as Turkey and Iran, and the rise of China, which now disputes the United States' global leadership. Naturally, the US's "pivot to Asia" calls into question the priority NATO gives to Europe's security.

However, common security and defence policy (CSDP) operations are becoming increasingly rare . EU Member States agree on the need to do more collectively. But they are still struggling to be more specific and operational in a sovereign domain that requires unanimity, where interventions and investments are costly and where, on the eastern border, NATO appears as the only reliable solution.

A. A COMPASS DESIGNED TO RECONCILE ASSESSMENTS

To jumpstart a constructive review of EU security, in 2019 Germany proposed drafting a "strategic compass", a sort of white paper for EU defence and security , which we recommended in the report "European defence: the Challenge of Strategic Autonomy". 1 ( * ) Initiated during the German Presidency of the Council of the EU in the second half of 2020 and expected to be completed during the French presidency in the first half of 2022, this exercise organises a discussion among experts and representatives of the executive branches of all Member States on an unprecedented scale . It began with a threat assessment based on contributions from their intelligence services. Finalised in late 2020 by the European External Action Service (EEAS), the classified assessment was not approved politically , which avoided having to prioritise threats that are perceived very differently from one country to another.

On this basis, the discussion then revolved around four 'baskets': ' crisis management ' and ' resilience ' for the objectives, ' capabilities ' and ' partnerships ' for the means. A strategic review extended to resilience and partnerships seeks to provide an exhaustive response to the threats. The exercise avoids explicitly promoting the EU's 'strategic autonomy' and 'sovereignty', terms that still irritate certain Member States. The EEAS will provide a synthesis of Member States' contributions in the second half of 2021, and the final political discussion should be completed in March 2022.

What can we hope for from this approach, given the context of the US's and NATO's recent return to the international stage?

B. A COMPASS TO JUMPSTART THE CSDP...

The results of previous jumpstarts to the common security and defence policy , from the Lisbon Treaty (2009) and then the ' European Union Global Strategy ' (EUGS) in 2016, have been below expectations. At any given time, any process can be blocked due to a lack of a shared vision by the rule of unanimity.

1. An ambitious approach to capability, but which remains disappointing

The EU has developed many instruments to make up for its capability shortfalls and acquire a European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB) by encouraging cooperation. But, for the large part, Member States are orienting their investments according to their own strategic interests or those of NATO. They are also undertaking partnerships outside the CSDP, such as those between France and Germany (the future combat air system, future tank) or with the United Kingdom (Lancaster House). As a result, Russia, with defence spending nearly four times less than the EU, discredits the CSDP on the eastern border in the eyes of certain Member States .

a) First avenue: better fulfil the potential of each of the instruments available

• The Capability Development Plan (CDP) sets the priorities in terms of the EU's defence capabilities. In the first phase, the European Union Military Staff (EUMS) uses the Headline Goal Process (HLGP) to identify the military resources needed for the five illustrative scenarios go smoothly. By reconciling these needs with the forces that the States report providing to the EU, the EUMS makes an inventory of gaps in capability, based on which the European Defence Agency establishes the CDP.

However, the Member States only report a small share of their capabilities here, compared to around half as part of the NDPP, the NATO Defence Planning Process. This 'under-reporting', which reflects a hesitancy towards the CSDP, reduces the reliability of the EU's capability process . Furthermore, the HLGP's most demanding scenario, which lacks credibility given that it provides for the deployment of 60,000 soldiers, leads to targets that are totally unreachable. In France, the Ministry of the Armed Forces supports adding a sixth, more realistic scenario , that resembles Operation Serval. It would be based on the deployment of just 5,000 soldiers but would still be very demanding in terms of equipment in order to fight in a hard-to-access environment.

• The CARD (Coordinated Annual Review on Defence) presented by the EDA gives a complete overview of Member States' spending and investments, including research. It allows us to see their defence planning and the development of their capabilities while listing the gaps with regards to the CDP. This inventory is intended to facilitate cooperation on capabilities. In November 2020, European defence ministers approved the first CARD , which criticised a ' costly fragmentation ' and identified 55 possibilities for multinational cooperation in the military field and 6 ` next generation capabilities as priority areas' . We fear that the Strategic Compass, as a parallel process, encourages a certain 'wait-and-see' approach.

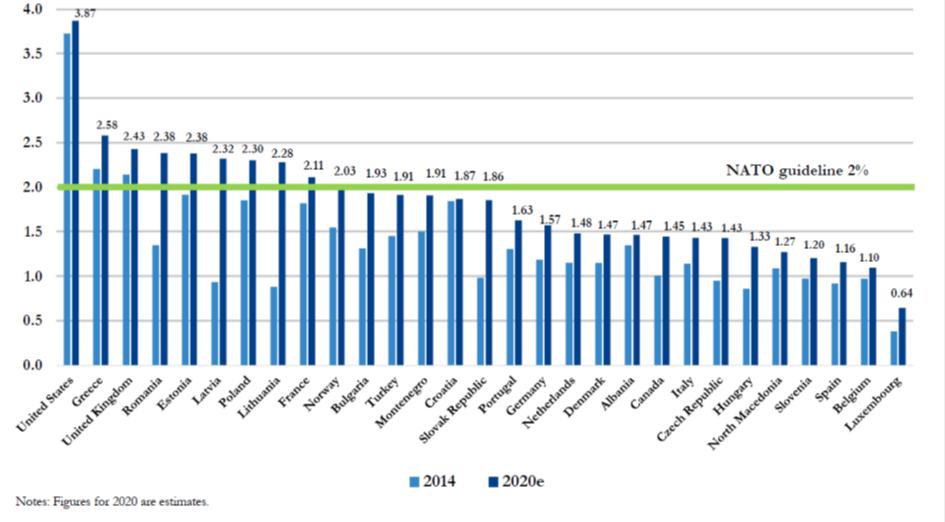

• The Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) , established in late 2017, seeks to increase defence spending by adopting NATO's 2014 objective for each Ally to allocate at least 2% of GDP to defence , with 20% of that for investments, and to provide a framework for cooperative projects in operations and equipment to increase European capabilities. PESCO, which also includes smaller countries, already includes 47 projects of this type. But the results remain mixed , with unequal achievements that call for being more selective with projects and an openness to third countries since 2020 that requires vigilance . This is particularly the case as regards the US's ITAR (International Traffic in Arms Regulations), which prevents the sale without their consent of equipment that includes American components.

• With the new European Defence Fund (EDF) , the Commission is looking to support investment in defence research and the development of shared technologies and equipment, including PESCO projects. Non-EU member countries are not eligible for the fund. With €8 billion for the 2021-2027 period, a much greater amount than the instruments it replaces, this fund is real progress , but its success could be hindered by the tendency of many Member States to see it as a redistribution fund.

b) Second avenue: improve the interactions between available instruments

In short, the CDP covers the list of priorities that Member States want to set by vaguely taking inspiration from a list of capability shortfalls established based on barely realistic scenarios and statements that lack sincerity. However, it does provide structure. The philosophies at work should interact in a better way : the EUMS with the illustrative scenarios, the EDA with the CDP and the CARD, and the Commission, which organises industrial cooperation via the EDF. All while respecting the constraint of aligning with the timeline of NATO's capability planning. Finally, it would be good to integrate aspects of the EU's capability process in national planning.

2. An operational approach that is running out of steam

Out of 17 missions and operations under way, three so-called 'executive' military operation involve combat forces: Althea (2004), Atalante (2008) and Irini (2015). That leaves three 'non-executive' military operations, which are training missions (EUTM), and 11 civilian missions.

a) First avenue: overcome the principle of unanimity

• The current easy option: ad hoc coordination : to act quickly, Member States--especially France with missions like Agenor and Takuba--are more than willing to intervene outside the CSDP. In doing so, they deprive themselves of its benefits (command, financing, political legitimacy) and the participation of certain Member States. Germany, for example, is legally prohibited from participating in an operation without a UN, NATO or EU mandate, except for certain preventive actions.

• The avenue of automaticity in case of aggression : the Strategic Compass exercise seems to reveal a new consensus for the mutual defence clause of Article 42.7 TEU, invoked just once, by France after the Paris attacks in 2015.

• The avenue of facilitated consent for greater flexibility : Article 44 TEU allows us to imagine that a Member State could propose a 'turnkey' operation conceived with a few other partner States. This would save time in the pre-studies and discussions between Member States with a view to establishing an operation concept. Another avenue, put forward by France, is that of 'bricks' of cooperation that the CSDP could provide to a national operation, to an ad hoc European cooperation such as Takuba or Agenor, or to a NATO or UN operation.

• The avenue of bypassing institutions : outside the CSDP and the EU, the studies conducted by the 13 Member States of the European Intervention Initiative (EII) favour the emergence of a common strategic culture. Other multinational initiatives in Europe seek to create a quick response force : Eurocorps, Franco-German Brigade, Combined Joint Expeditionary Force (CJEF), Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF).

• The avenue of a hard core: establish a European Security Council? Since EU Member States are struggling to agree on defence issues, we could wonder whether to establish a 'vanguard' outside the CSDP. This option, presented several times by Angela Merkel as a 'European Security Council', was ultimately supported by Emmanuel Macron (joint statement of 19 June 2018).

b) Second avenue: improve operations and their context

• Improve mission quality

The force generation derived from the three EUTMs suffers from incomplete training. Civilian missions mainly suffer from unsatisfactory expertise in regard to the needs due to a lack of ambition from contributing States. In Africa, these gaps are becoming even more problematic, given that Russia, China, and even Turkey are now there as rivals.

• Accelerate force generation by making battlegroups sustainable

Established in 2006, the EU Battlegroups are each made up of 1,500 troops and are intended to provide a military presence in groups of two. However, they have never been deployed and are often unavailable .

Collective financing through the European Peace Facility would be incentivising. During the discussions on the Strategic Compass, a small majority of States co-signed a French non-paper proposing a "first entry force" in line with the sixth scenario (see above). Its core could be two big battlegroups with land, air and maritime components.

• Better funding for missions, the European Peace Facility (EPF)

With €5 billion for the 2021-2027 period outside the EU's regular budget, this year the EPF replaces the Athena mechanism, which funds certain shared expenses for CSDP operations, and the African Peace Facility (APF). The EPF materialises progress that was anticipated by allowing for direct military aid, even of a lethal nature , which will help to improve a crucial point of training in EUTMs.

• Europeanise military command

For the command of CSDP military operations, it is possible to employ either:

- the 'Berlin Plus' agreements (2003) , which allow the NATO command structure to be used, which was the case in Macedonia and Bosnia (where the Althea operation still uses it); using these agreements again currently seems unlikely,

- an 'autonomous European Union operation' that relies on a national military staff, chosen for each operation from among five eligible Member States, each time requiring a period of familiarisation with how the relevant European bodies operate,

- or, since 2017, for non-executive military operations, the MPCC (Military Planning and Conduct Capability), led by the head of the EUMS.

The three EUTMs are overseen by the MPCC. But the human and material situation at the MPCC does not always allow it to assume its role perfectly. The head of the EUMS is not expected to declare it fully operationally capable until the end of 2021, one year behind schedule. Later, it would be beneficial to extend the MPCC's scope to executive military missions. This would provide a military staff for planning, otherwise referred to as an 'OHQ', 2 ( * ) for all military missions. In this perspective, France supports maintaining a single command for the EUMS and MPCC in order to preserve the unity of capability reflections and a satisfactory balance between the Council and the Commission. Indeed, certain Member States would like to call them into question.

• Provide information to military command

European intelligence is very patchy. Here, France advocates using the EU's electronic intelligence tools, including SatCen (the satellite image analysis centre), and increasing information gathering capabilities.

C. ... AND RESIZE THE EU'S ACTIONS TO MEET ITS SECURITY NEEDS?

1. 'Resilience', a necessary and consensual objective supported by the Commission

Resilience is about preserving access to contested strategic spaces such as cyberspace, space, seas and airspace. It is also about reducing our industrial dependence in security and defence and strengthening our access to critical technologies and strategic materials. Finally, it is about ensuring our economic, health and climate security. The Commission, which now seeks to be 'geopolitical', is very active on these issues. A change of dimension can already be seen in the negotiations with pharmaceutical laboratories, the European recovery plan, and the actions towards Russia and China. In 2020, the DG DEFIS (Defence Industry and Space) was created, headed by Thierry Breton, demonstrating the EU's new propensity to leverage its economic power to strategic ends.

2. 'Partnerships' that should be nurtured carefully

Reinforcing a stature as a geostrategic player implies making many partnerships. The partnership with NATO has special weight, to the point that it is provides more structure for CSDP than the latter does for it.

a) NATO: the central issue of 'Who does what?' with the EU

• NATO guarantees the security of the EU's Allied territory through the mutual defence clause in Article 5, the very foundation of the alliance. It is also responsible for managing crises outside its members' territories, integrated into its strategic concept in 1999.

The EU, with a CSDP that meets the level of ambition set out in Helsinki in 1999, ought to be able to manage crises in its nearby environment without NATO. The EU cannot count on the consent of all non-EU allies (Turkey opposes certain operations in the Mediterranean) nor on their aid (the United States may not want to get involved). But the CSDP's potential is insufficient , so much so that the distribution of roles tends to end up as follow:

- NATO defends Europe's territory and manages crises at the top of the spectrum, both involving the Eastern border,

- the European Union responds to other security challenges around Europe--stabilisation and peacekeeping operations, controlling migrant movements--which mainly involves crises on the southern border.

This complementarity between NATO and the EU must be reaffirmed and clarified with a realistic level of ambition, which would lend credibility to Europe as a power, possibly based on the French first entry scenario (see above). Whatever the case, without drawing up a detailed, rigid distribution of roles that could prove counterproductive, the Strategic Compass should finally clearly state what the EU must know how to do.

In addition to the 'Berlin Plus' agreements (see above), the relationship with NATO should be seen in terms of its many partnerships, which have been revived since the Warsaw summit in July 2016. NATO and the EU now exchange real-time alerts on cyberattacks, participate in each other's exercises and collaborate in their response to migration crises. Military mobility, a major chapter of cooperation for both organisations, is what justifies the participation of the United States, Canada and Norway in a specific PESCO project.

b) USA, UK, China, Indo-Pacific, Africa

Joe Biden reversed most of the decisions criticised by the EU. The quality of the relationship with the United States has been restored, but there are certain constants that should lead us to beware following them blindly : the pivot to Asia and their desire to impose their approach to China, the promotion of a capability integration within NATO that benefits their military-industrial complex (thus at the expense of the EDTIB), economic competition, extraterritorial sanctions, ITAR regulations, etc.

Without giving up on establishing a privileged security and defence link with the United Kingdom , we must be realistic about the post-Brexit appetite for European mechanisms of a country so strongly anchored in its transatlantic partnership. Its latest strategic review was drawn up with NATO and the US in mind, and the UK is seeking to inject into the Alliance the resilience issues that the EU is committed to addressing.

China poses a growing challenge to the EU, especially on issues of resilience: digital sovereignty, misinformation, industrial capacity, competitiveness, market access, risk of denial of access to sea lanes, especially in the straits. The initial enthusiasm of the 17+1 member countries is waning. There is an increasingly widespread conviction that we must 'act as one' towards China, which is described as being at once a rival, competitor, and a partner and which is disserved by a now-conspicuous hubris. Dealing with the 'China issue' solely through NATO would be a pitfall that risks allowing America to interfere in the EU's trade policy. Therefore, the EU must quickly develop a strategic line that requires reciprocity in economic matters. Indeed, China could takeover Former President Trump's role as a driver of the EU's 'geopoliticisation".

In essence, the Indo-Pacific is another way for the EU to deal with China, which is likely to deny certain maritime access to this area that is home to 60% of the world's population and the most dynamic GDPs. But there is a risk that such a broad security and defence issue could be more appropriately dealt with in the NATO framework , together with the maritime powers of the United States and the United Kingdom, at the risk of reducing the EU's autonomy in dealing with China.

Finally, the EU must confirm a " pivot to Africa " where, in a newly competitive environment (China, Russia, Turkey), stronger cooperation aimed at consolidating institutions, developing infrastructure, educating the people and combating the crisis-induced poverty will promote growth and security, aid in the fight against terrorism, and help control emigration.

II. A COMPASS THAT MIGHT BE POINTING A LITTLE TOO FAR WEST

A. THE GREAT RETURN OF ATLANTIC AFFINITIES ...

1. NATO's renewed credibility in the face of a CSDP weakened by Brexit...

The election of Joe Biden and the announcement that the United States is resuming its role as the world's policeman, notably within the framework of a NATO reaffirming its role as the Allies' protector, are reassuring. Similarly, the appointments of Antony Blinken and Karen Donfried, Deputy for European and Eurasian Affairs, were welcomed throughout the European Union. Reassured, European decision-makers often aspire to resume the course of the traditional Atlantic relationship.

Compared to the pre-Trump situation, Brexit adds an argument for tipping the balance in favour of NATO , since the UK is the ally with the highest defence spending ($60 bn), after the US ($785 bn) and ahead of Germany ($56 bn) and France ($50 bn). EU countries now account for only one fifth of the defence spending of NATO countries .

2. ...by the health crisis and the ensuing budget impacts...

The health crisis has resulted in heavy spending to support the economy while focusing security attention on the lower end of the spectrum and resilience. Thus, EU Allies will be more likely to rely on NATO for the upper end of the spectrum, especially as they are forced to make budget adjustments . These may entail capability and operational sacrifices , for which better coordination would be unlikely to compensate.

3. ... and by political configurations likely to become less favourable

The German elections in September 2021 and the French elections in the spring of 2022 could jeopardise the EU's mobilisation for security and defence. In Germany, the elections could result in a new coalition that includes the Greens, who are historically more suspicious of armed intervention and perhaps more intransigent towards China and Russia - as is the US.

B. ... DESPITE INCREASINGLY DEMANDING AND COMPLEX COORDINATION WITH NATO

1. Potentially different geostrategic aims

China is an ultimate threat for the US (which sets the agenda for NATO), not for the EU . The European Union's economic and strategic interests may justify choices of cooperation, including with Russia, that the United States might not approve of. Conversely, Turkey, against which the EU may have an interest in acting, is part of NATO, which does not want to weaken itself by alienating an ally whose geographical position is considered strategic by the United States.

2. The intangible 'NATO umbrella'

Joe Biden has a very slim majority in Congress, especially in the Senate, which weakens his international policy and gives reason to worry for the upcoming elections. The midterm elections will take place in little more than a year, and presidential elections in a little more than three.

The Pax Americana, renewed via NATO, could be shorter than hoped. It should be seen as a chance for the EU to buy time to organise its security in a more comprehensive way.

3. The imminent perspective of a 'great leap forward'

NATO is showing great ambitions, as evidenced in particular the NATO 2030 agenda , approved by the Allies in Brussels on 14 June 2021. In the past few months, NATO's work has developed a 360° defence strategy , summarised herein.

The Agenda suggests using Article 5 in case of a cyberattack, which merits clarification. These actions could come from countries where the EU and the United States do not share the same risks or objectives, and identifying the source country requires caution. Furthermore, it considers resilience in its widest sense, going so far as assigning objectives to Allies and monitoring their achievement.

If all the Agenda's prospects come to pass, the resilience that the EU seeks to orchestrate could be overshadowed by a NATO-led resilience, just as the CSDP barely survives alongside the Alliance. While the immense power of the American army may explain this, nothing would justify it given the EU's resources.

4. NATO's capability advantage

Europe's capability planning is less directive and incentivising than the NDPP (NATO Defence Planning Process), and is less adhered to , particularly by Member States without a military programme act and which defend their military budgets solely on this basis.

This raises the issue of the coherence among the commitments of countries in the EU and in NATO. 38 of the 47 PESCO projects meet NATO priorities to a certain extend. However, it is not NATO's role, through the NDPP, to have a say in the commitments made within the EU. In the same vein, modelling Europe's norms and standards developed through PESCO on NATO norms and standards could jeopardise the establishment of an EDTIB. Reserving EDF funding for European projects is a partial safeguard. But the Agenda plans to set up a NATO fund for innovation .

5. The concurrence of strategic reflections

The Strategic Compass , which envisages a partnership approach to NATO, is not intended to be a local version of the "Strategic Concept" that the Alliance is working on. On paper, the reflections are not taking place at the same time, nor are they being completed simultaneously, since the Strategic Concept is expected to be released in summer 2022. The schedules were planned so that the Strategic Compass would not be influenced. But NATO, as requested by its Secretary General in the framework of the NATO 2030 strategy, is intensifying its work and reflections. According to certain observers, everything is happening as if NATO were in a race. Its options risk heavily influencing the Strategic Compass --which would suit the desires of countries such as Poland or certain Baltic countries. A political dialogue between the HR/VP and the NATO Secretary General would be very useful to arrive at the necessary coherence between the two exercises while ensuring the autonomy of the Strategic Compass approach . But currently, nothing indicates that such a dialogue could take place.

III. A STRATEGIC COMPASS THAT HAS BECOME RISKY

A failure of the Strategic Compass would be very damaging for the CSDP : experience shows that disillusions in this area push back any possibility of progress for many years. Here, we express our great regret as to the methodology: concertation and discussions on the Strategic Compass were not extended to parliaments. This deprives the Strategic Compass of a means to enrich and deepen the audience among Europe's citizens, whose absence will weigh on the process's completion in early 2022.

A. THE RISK OF AN UNAMBITIOUS DOCUMENT

The stated reaffirmation and strengthening of the Atlantic security guarantee weigh on the ambitions most Member States have for the CSDP. The threat assessment that they will accept politically may focus only on the most consensual, hybrid and technological ones. This could favour resilience over crisis management and capabilities that are solely industrial and technological. For the CSDP, this would mean losing the two years spent on drafting the Strategic Compass. We might then add the years following the publication of the Strategic Compass, which is still being presented as binding for Member States.

An incomplete Strategic Compass could be relativised--and made presentable--through binding initiatives to improve only non-executive civilian or military missions , which Germany prefers to executive missions. But we must oppose any attempt to promote the use of the military within borders to assume, in the name of resilience, a generalist role that would permanently distance them from their primary mission.

B. THE RISK OF A DOCUMENT GEARED SOLELY TO NATO'S NEEDS

There is a real risk that the document will fit the mould of NATO's Strategic Concept. The compass would not offer anything that could be seen as a duplicate of NATO resources or as distancing itself from NATO's ambitions, whether in terms of the military or of resilience. Major expectations would then revolve around a deeper partnership with NATO.

We fear that the Strategic Compass's ambitions would be partly within the hands of the United States. Indeed, the signals that they send in terms of the room allowed for EU autonomy will be interpreted and followed very closely by the most Atlanticist Member States through to the very end of the process.

C. THE RISK OF A MORE AMBITIOUS DOCUMENT WITH LITTLE EFFECT

However, the final document could include interesting opportunities , especially in terms of resilience concerning contested spaces, that should be made permanent. In terms of the CSDP, the first entry force , supported by Josep Borrell, would be a significant advance that could be considered globally acceptable if it is conceived to avoid any duplication that could offend NATO or the United States.

This is why a mechanism for political monitoring and support should be implemented, in line with one of France's key concerns.

D. THE RISK OF A DOCUMENT THAT BECOMES A STRAITJACKET IN A CRISIS

As the health crisis has shown, the EU is capable of finding willpower when events require. A very formal document , especially if it assumes a minimal capability for action, could prove counterproductive in a crisis. This reasoning applies to relations with NATO, which the compass should not make too rigid. Similarly, less flexibility in our relations with Russia, Turkey, China and certain North African countries could be damaging. Updating the Strategic Compass every five years would allow us to adjust it to the geostrategic reality while limiting all the risks stated above.

E. THE ADDITIONAL RISK OF FRANCE BEING SEEN AS IN CONTROL

France , perhaps worried that a disappointing Strategic Compass may tarnish its presidency of the Council of the EU, should take care to avoid indulging its penchant for spectacular statements and promoting concepts. If it does so, it would only upset its partners and undermine the process.

Nevertheless, France is still respected, and its assessments are eagerly awaited: it will therefore have to stand by its convictions, explain them and try to convince other countries, in the interest of all EU countries .

INTRODUCTION

When the opposition between the Western and Soviet blocs ended, revealing a possible 'end of history', 3 ( * ) the 1990s saw the rise of liberal democracy and the market as vectors of growth, trade and peace that would lead to a drop in world conflicts. But the 21 st century opened a new era of uncertainty.

The beginning of this century has been characterised by the emergence of new dangers - in particular risks from jihadists as well as cyber and a whole range of new so-called "hybrid" threats - by the new assertiveness of powers with destabilising aims - Russia, Turkey and Iran, to focus on the recent period and our immediate environment - and by America's world leadership that is gradually being challenged by the spectacular rise of China. Obsessed with its Asian competitor, the Obama administration began a "pivot to Asia" in 2011 which, in the long run, called into question the priority NATO gives to Europe's security.

It is true that, since the 1990s, the European Union had gradually established a common security and defence policy (CSDP). But its ambitions were limited. Most Member States, either because they felt they faced too great a threat, particularly on the eastern edge, because their defence capabilities were too weak, or both, essentially continued to rely on NATO's security guarantee to the Allies. This guarantee, which is primarily provided by the Americans, whose colossal military expenditure - by far the largest in the world - represents 70% of all Allied spending, was deemed immeasurably more reassuring, convenient and, in short, economical.

Due to an awareness of the scissor effect resulting from an increased number of threats--not all of which fall within NATO's remit--and the risk of a security guarantee within the Alliance that is less unconditional from the Americans, European Union Member States have recently been encouraged to do more for their security.

The Americans themselves are directly calling for better 'burden sharing' on defence between Allies, so much so that each of them agreed to spend 2% of their GDP on defence within 10 years at the NATO summit in Newport in 2014. This resulted in a reversal of the downward trend in defence spending among EU countries from 2015.

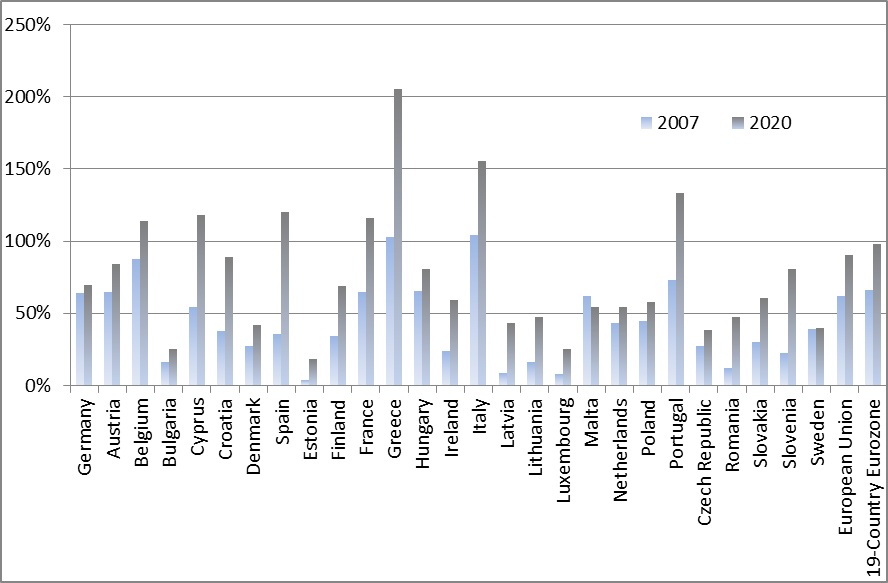

DEFENCE SPENDING AS A SHARE OF GDP IN 2014 AND IN 2020 (%) 4 ( * )

%

The Trump administration openly called into question America's guarantee of transatlantic coverage. Once the shock had passed, Europeans increasingly asked themselves if the time was right to effectively jumpstart the CSDP to prepare for any eventuality.

This would be no mean feat for a policy that is often criticised for its complexity, illegibility and even relative ineffectiveness (in the sense of added value compared to national initiatives, even combined), and for the indifference of European citizens towards it.

Ultimately, the Biden administration strongly reaffirmed the US commitment to NATO. The European desire for genuine autonomy in security and defence matters could be jeopardised as soon as it was strengthened.

However, the threats outside the Alliance's traditional remit remain. Furthermore, Trumpism is not dead; there is no reason to expect that it will not continue to prosper and offer an electoral proposal that will convince a majority of Americans, if not for the upcoming midterms, then the next presidential elections.

What would happen to NATO's protection if it had to weather four more years of US suspicion towards their European allies? Four years of an American foreign policy that relies on challenging multilateralism? Four years of uninhibited middle powers, using a range of new conflict powers, feeling freer than ever to engage in all sorts of actions in order to unite domestic opinion put to the test by economic difficulties and attacks on freedom?

Today, the European Union is far from able, or even wanting, to take on the role of the world's pole of stability, which would combine a respect for multilateralism and human rights with the universal respect that a leading-rank power inspires. The success of the Biden administration on the domestic front is therefore crucial, since it could determine the political sustainability of the return of the United States to the world stage, which Europeans are now seeing with relief, and the advent of a new Pax Americana - whether under the UN or NATO banner.

Still influenced by the sudden American dawn, the Europeans are betting on this favourable scenario, assuming that, even today, European defence--in the sense of a defence of European territory--as envisaged by the Treaty of Amsterdam (see below) can only be foreseen in the distant future.

However, even in this optimistic scenario, some Allies--such as the United States, the United Kingdom or Turkey--might not want to follow the EU in a crisis management operation outside its territory, which the EU would nonetheless deem indispensable for its security. Let's remember the Obama administration's decision not to intervene in Syria in 2013. The US does not want to engage directly in the Sahel either for the moment. The increase in the risks in a more unstable, unpredictable world, a harbinger of a possible return to demanding, so-called 'high intensity' operations in external theatres that interest the European Union far more than NATO, is a shared observation. However, given its current desire, capabilities and organisation of its security and defence, everything leads us to believe that the European Union would struggle to establish an effective, proportionate intervention force.

Can the European Union give itself the resources to take on this minimal crisis management role, in supplement to the role that NATO plays for its territorial defence? It has been trying for thirty years, more or less.

Here, it is not useful 5 ( * ) to go back to the project for a European Defence Community (EDC) that France rejected in 1954 or the Western European Union (WEU) set up the same year. 6 ( * ) In the contemporary international order, the shared acknowledgement of the need for an effective European security and defence apparatus goes back to the wars in Yugoslavia (1991-2001), which, with some 150,000 deaths in 10 years, offered the distressing spectacle of a Europe incapable of acting on its own doorstep without turning to NATO, i.e. the United States.

The Maastricht Treaty, which came into force in 1993, introduced the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) as the second pillar of the EU. In 1997, the Treaty of Amsterdam gave the CFSP the task of ' the progressive framing of a common defence policy, which might lead to a common defence ', with the goal of being able to carry out the Petersberg tasks. 7 ( * )

At the Franco-British summit in Saint-Malo in 1998, the United Kingdom lifted its veto on the creation of European crisis management capabilities. In 2003, the first EU missions and operations took place .

Then, in 2004, the Treaty of Nice specifically established the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP), which was succeeded by the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) , an integral part of the CFSP, in the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009. The position of High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HR/VP) was created. They have authority over the European External Action Service (EEAS), established in 2011, which manages the EU's diplomatic relations with non-member countries and conducts the CFSP. Since 2016, special attention has been paid to CSDP instruments with a new flurry of initiatives of varying outcomes, bearing in mind that CFSP/CSDP decisions are still adopted in principle by unanimity.

Of course, a defence and security policy cannot be conceived without a strategic document, and so in December 2003 the " European Security Strategy " was adopted, which even then was based on a common threat assessment and defined objectives to promote the European Union's security interests. It was revised in 2007 and succeeded by the "European Union Global Strategy" (EUGS), adopted on 28 June 2016, which is now the EU's updated doctrine for improving the effectiveness of the defence and security of the Union and its Member States. 8 ( * )

All in all, the record of thirty years of summits, meetings, votes, treaties, plans, establishment of bodies and instruments of all kinds to strengthen and organise the security and defence of the EU remains disappointing. Thirty years of effort have not produced a detailed and shared diagnosis of the threats facing the EU, forces that can be immediately mobilised to respond to a crisis, effective decision-making procedures for launching an operation, nor a capability process that provides sufficient incentives to make up for the EU's shortcomings in terms of the availability and production of the necessary equipment. Despite some promising advances, it has largely been thirty years of posturing.

However, there is now a general agreement that Europe needs to do more in the field of security and defence in the face of the growing scope and variety of threats. But experience shows that divergences never fail to appear whenever the time comes for specificity on the issues that generally require unanimity.

So, the time seemed right to tackle once again all the outstanding problems while looking for an approach that was new in both its method and breadth of vision.

This is the spirit in which Germany proposed in 2019 the drafting of a 'strategic compass', which would be a sort of white paper on the EU's security and defence.

Launched under the German Presidency of the Council of the EU in the second half of 2020 and expected to be finished during the French presidency in the first half of 2022, this exercise organises a reciprocal exchange between experts and representatives of all Member States on an unprecedented scale.

It starts with an assessment of the threats on all fronts , from conventional conflicts to supply shortages--a risk highlighted by the health crisis--to attempts to deny access to certain spaces, misinformation, and computer hacking. To identify the measures to take as a result of these threats, the approach widens its focus : beyond the traditional areas of crisis management and the civilian and military capabilities that this requires, it is structured to deal equally with resilience , favouring a more comprehensive response to the variety of threats, and with partnerships , including NATO. Indeed, it seemed necessary to tackle these four chapters together in order to promote the emergence of a truly geopolitical European Union, strong and free to decide its own destiny, which could exist on the geopolitical stage.

What phase have we reached in the process of this strategic compass, which indeed seems decisive for the future of Europe and our collective security? What hopes can this approach reasonably raise? Does it not entail certain risks --particularly in the light of recent international developments-- and how can we guard against them, where appropriate?

Looking for answers means tackling complex issues that are either dealt with in a piecemeal and technical manner by experts speaking to other experts, or in a more political way but which is based on arguments of authority. Sometimes--and this is typical of French leaders--these issues give rise to clear analyses that lead to strong proposals, but which disregard the range of sensitivities that exist among European partners. There is a risk that these proposals will be received, with an often-perceptible annoyance, as pro domo pleas to reinforce an autonomy that matches the French vision of these issues, but which is in reality unrealistic, even dangerous.

This is the purpose of this report is to provide reasoned answers to these essential questions , placing them in their context so that they can be understood by Europe's citizens, whose future is at stake.

Shedding light in this way on the terms of the debate could strengthen the ambitions of the Strategic Compass for the benefit of a common good: a Europe that is free yet respectful of its commitments, a Europe that is strong yet aware of its limits, a Europe that is both prosperous and protective.

*

To gather input for their work, the rapporteurs held hearings with French and European administrations, experts, members of the European Parliament and officials in the defence ministries of other EU Member States (list in the annex). They also sent a questionnaire (also in the annex) on the Strategic Compass to all French embassies in EU countries.

A GENERAL PRESENTATION OF THE STRATEGIC COMPASS

The Strategic Compass is intended to be Europe's new defence doctrine that will match the EU's actual capabilities for action with its 'level of ambition' --which no doubt merits clarification--by defining the security and defence initiatives to take in the next ten years.

The EU's 'level of ambition'

The EU's 'level of ambition' includes a political aspect and a military aspect. It results from several texts drafted between 1999 and 2016.

Politically, the EU defined its level of ambition most recently in the EUGS and its implementation plan for security and defence. The EUGS mentions three strategic priorities for security and defence: react to external crises and conflicts , reinforce partners' capabilities , and protect the Union and its citizens .

Militarily, these objectives require 'full spectrum defence capabilities'. However, the EUGS has not led to a complete review of the types of operations that the EU and its Member States should be able to undertake. Thus, the EU's current military level of ambition is still derived from the TEU and headline objectives.

Under the TEU, the EU and its Member States should be able to carry out the following operations: 'joint disarmament operations, humanitarian and rescue tasks, military advice and assistance tasks, conflict prevention and peace-keeping tasks, tasks of combat forces in crisis management, including peace-making and post-conflict stabilisation' .

The Strategic Compass will comprise two main contributions: a shared assessment of the EU's threats and vulnerabilities and orientations and objectives for 2030, itself organised into four sections or "baskets" that will structure the EU's stance in its strategic environment: crisis management, resilience, capabilities and partnerships.

This work was formally launched by the Foreign Affairs Council in defence format on 17 June 2020. It will continue until the French Presidency of the European Union (FPEU) in the first half of 2022. The roadmap initially set out is on track to be respected:

1. June 2020: process launched

2. November 2020: threat assessment finalised

3. First half of 2021: discussion of resources and objectives, Member State contributions

4. Second half of 2021: synthesis with a view to a draft Strategic Compass

5. Political discussions and adoption of the Strategic Compass in March 2022

The drafting of the compass and related preliminary work is led by the High Representative/Vice-President of the European Commission, Josep Borrell, in close cooperation with the Member States. Converging Europeans around shared interests of defence and security is this work's main challenge.

• The threat assessment

Drawing up an inventory of threats means recognising that, perhaps not enemies, but at least adversaries and shared risks exist. Each Member State carries out this type of assessment regularly, as does NATO, which overhauls its 'Strategic Concept' every ten years or so.

However, this is the first time the European Union has conducted a deep, ten-year threat assessment. It was finalised on 26 November 2020. Based on contributions from intelligence services, this assessment is presented as a raw, classified, uncertified document produced by the European External Action Service (EEAS) and coordinated by the EU Military Staff (EUMS). 9 ( * ) It is divided into three parts: regional threats, transversal threats and threats to the EU. It also includes a prospective analysis component to identify how threats may evolve in the next five or ten years.

• Europe's response to these threats: setting guidelines and objectives for 2030

Member States were invited to present their contributions to the Strategic Compass in the first half of 2021. In February, the EEAS produced a scoping paper, an initial synthesis of the contributions organised into four baskets, intended to trigger new proposals in an iterative approach. This document was not publicly distributed either. At the core of the process, contributions in the form of 'non-papers' 10 ( * ) from certain Member States fuelled discussions in 'workshops', groups whose size varied depending on the subject discussed (by the non-paper) and which were made up of experts and representatives of Member States. These 'non-papers' were co-signed by varying numbers of Member States and then handed to the EEAS. The work's progress was punctuated by meetings of the Council of Ministers.

We can detail the content of each basket of the Strategic Compass as follows:

• internal and external crisis management : through this basket, the goal is to become a 'security provider' that proves to be more 'capable and effective' in the face of crises, to improve operational response and reactivity; here, we target European external missions and operations.

• resilience : this consists in securing access to shared assets (cyber, high seas, space), in assessing strategic vulnerabilities in defence and security (destabilisation, hybrid threats, threats to critical infrastructure, procurement chains, etc.), in strengthening mutual aid and solidarity between Member States (clauses in Articles 222 TFEU 11 ( * ) and 42.7 TEU 12 ( * ) ). This is a rather new chapter that seeks to protect shared values, institutions, tools and assets.

• developing capabilities : more specifically, developing the necessary civilian and military capabilities, improving the capability development process, promoting innovation and technological sovereignty, in keeping with the main capability tools implemented recently: Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), the European Defence Fund (EDF, see above), etc.

• partnerships : this section covers the structure of cooperation with certain international organisations (UN, NATO, OSCE, African Union, ASEAN, G5 Sahel, etc.), the development of a strategic approach with third countries, and aid to EU partners so they can manage their own security.

The first two baskets set out the ambitions, the other two cover how they will be implemented. In other words, the first two baskets cover the objectives, the two others, the means.

There is a lot of overlap between these chapters, and there is no guarantee that the final product will be organised in this way. The EEAS will draft its synthesis in the second half of 2021. This draft Strategic Compass will be presented to the Foreign Affairs Council (Defence) in November 2021.

• Finishing the process

The Strategic Compass will be finalised with a view to adoption in March 2022, during the French Presidency of the Council of the European Union (FPEU) in the first half of 2022.

• In this work, the most salient specificities of the French approach , as signalled by the Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, would be the following:

First, France does not intend to lock itself into a pre-established plan. For example, it drove making the issue of access to shared spaces (cyber, space, maritime spaces) a key one by triggering a workshop. Given the increase in risks, France feels that the European Union can help stabilise access to the spaces through normative action.

Secondly, it will be particularly attentive to how the compass is implemented. France will work to develop an implementation plan by 2030 with the presidencies that will follow: Czechia in the second half of 2022 and Sweden in the first half of 2023.

Finally, it is important to France that there is a good coherence between the Strategic Compass and NATO's Strategic Concept , which is being revised simultaneously, without the former conforming to the latter. Furthermore, while France wants to reaffirm the Allies' collective defence through NATO, it does not want the result to be a rigid 'sharing' of responsibilities that it considers dangerous, judging that it is up to countries that are members of both the EU and NATO to make sure their respective actions are coherent on a case-by-case basis.

I. A COMPASS FOR A FREE, STRONG AND PROTECTIVE EUROPE

A. RECONCILING ASSESSMENTS...

In the former Eastern Bloc, the Baltic States, Poland and Romania are focusing their attention on Russia and their expectations on NATO and the United States, rather than the EU.

Meanwhile, Southern Europe, France and Belgium are primarily sensitive to the risks of terrorism and migration, represented by the Sahel, the destabilising influence of Turkey's policies and the conflicts in Syria and Libya. Given NATO's overall refusal to take action in these theatres, these sensitivities come with the conviction that the EU must achieve its 'strategic autonomy', a concept on which Italy, Spain, and even part of Germany tend to agree.

Finally, countries like Austria, Ireland and Sweden traditionally feel distant from traditional threats; they do not belong to NATO and take a neutral stance militarily to security matters.

These divergences of view, which also apply to the attitude towards China and Libya, may seem deep, even insurmountable. But the stances that make up the range of the European Union's geostrategic sensibilities are not written in stone .

1. An accumulation of threats that calls for pooling

a) A growing number of increasingly varied and serious threats

Under the Trump administration, Europeans were stunned by the questioning of the automaticity of America's contribution through NATO to the collective security of its European members. Donald Trump explicitly made the United States' guarantee of the security of certain Member States via NATO dependent on their trade behaviour, using US protection as a bargaining chip - in particular against Germany in order to get it to reduce its exports.

At the same time, the Europeans were exposed to threats that were more specific, numerous and varied and which called for a common approach.

The risks of destabilising regional conflicts on the European Union's doorstep--such as in Syria, Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh--which could justify resorting to the CSDP as part of a crisis management operation, grew. A new assertiveness on the part of neighbouring middle powers-- Russia, Turkey, Iran--tensions over water and energy, climate change and food security are all circumstances that could precipitate or sustain such conflicts.

There were also proven aggressions, the nature of which fell within the scope of NATO's collective defence, but to which the Alliance struggled to provide a coordinated response because one of its members was involved: Turkey. Its attitude, its illegal actions to the detriment of Greece and Cyprus, against which France was the first to speak out vigorously, eventually led to a general condemnation, at least formally, within the EU.

There were other types of threats that replaced previous ones as they were identified, but which were not properly understood either by NATO or by the European Union, and that also called for organisation. The threat of terrorism, whether endogenous or exported, with its components of radicalisation and combat Islamism, is at the fore. The risk of migration causes concern, as do cyberattacks and misinformation, with active campaigns from Turkey, Russia and China. In general, China's rise has been accompanied by an increasingly intrusive and less friendly attitude that calls for as coordinated a response as possible.

Hybrid threats are a mix of the previous ones, resulting from security breaches that combine conventional and unconventional methods that can be diplomatic, military, economic or technical. They are ever-changing and hard to define, the work of regional or global powers seeking to extend their influence by using all the means at their disposal, including political and industrial espionage.

Under another angle, the use of chemical, bacteriological and nuclear weapons is also among the threats to the European Union within and outside its territory.

For around two years, 'resilience' issues such as access to contested spaces--especially maritime routes--and the control of investments in strategic sectors have aroused a fairly broad consensus. The health crisis, by highlighting the threats to the supply chain which could also seriously compromise the European Union's sovereignty, has put a spotlight on the notion of resilience.

As a counterpoint, the systemic threat posed by climate change, which has a direct effect in the Arctic and is already contributing to certain surges of migration in Africa, is also present but over a longer period of time, unfortunately with growing intensity each year.

b) The beginning of a certain convergence of views

The political context, if we focus on the Franco-German relationship, became favourable from 2017 onwards, with the conjunction of a French president, who was more pro-European than his predecessors, and a German chancellor who, under pressure from a Germany-demonising Trump, no longer hesitated to speak of the need for Europe to take control of its own destiny.

Europeans quickly came to agree that the environment had become more hostile than it had been in 2016, when the EUGS was established, which itself was quickly made obsolete since it had been published the same week as Brexit took place and six months before Trump's election. Its main virtue was that it brought about a moment of reconciliation (after strong divergences had emerged over the military intervention in Iraq) around a relatively low common denominator.

Consequently, they agreed on the need to give itself the means to be taken seriously and on the benefit of a new strategic document that would be a veritable white paper of European defence. Since it should be published in early 2022, after the new US administration is in place, it is likely that the Strategic Compass will become obsolete.

In general, Member States have progressively realised that meeting a global security objective is increasing difficult at the national level, but remains realistic at the supranational level, and yet NATO cannot cover all the risks . There is growing awareness that Member State sovereignty and European sovereignty reinforce each other more than they compete--an idea which may help to counter a populism that is harmful to the European construction in general and its defence and security policy in particular.

Of course, the Strategic Compass will never be able to iron out all the differences in approach between European partners, some of which appear to be insurmountable, particularly in military matters. In fact, if we look at Poland or the United Kingdom, the Trump period had mixed effects , as these countries displayed an extra level of eagerness towards the United States and energetically reaffirmed their Atlanticism, with unusually expensive acquisitions of American military equipment, which is directly explained by the prospect of securing their protection.

But, overall, the differences in approach have become smaller than often assumed.

As a positive sign, certain northern and eastern European countries have joined, or are about to join, Takuba 13 ( * ) --even if certain participants also see it as a way to gain experience alongside us to be more effective in their own territorial defence. For example, Poland, Romania and the Baltic States are participating in the Mali EUTM. 14 ( * ) How the Czech Republic and Slovakia perceive risks has evolved in recent years, to the point that they are showing greater interest in 'strategic autonomy'. In general, the Central European states seem ready for greater commitment within the CSDP. This is the case for cyberattacks, where Poland and the Baltic States are now promoting the idea of a European cyberdefence and a solidarity clause in this area, which amounts to a small breakthrough--even if certain changes in attitude in Poland and the Baltic States can be explained quite simply by Turkey's blocking of the NATO defence plan for the past several years. 15 ( * )

Reciprocally, France is present in Estonia with the Lynx mission in the framework of the eFP. 16 ( * ) The more the staff of the Member States work together, the more likely it is that their strategic cultures will converge.

2. A 'Strategic Compass' that is both inclusive and ambitious

In keeping with the German vision, which is very inclusive on security and defence issues, the Strategic Compass is based on a participatory approach whose primary objective is to leave no Member State behind. In constant cooperation with France in proposing non-papers and organising workshops, Germany insists that, in the Strategic Compass, discussions are as important as the final product.

From the outset, the risk in undertaking this process appeared non-negligible: that of a narrow final result, reduced to the broadest common denominator of 27 approaches which would remain very different, and which would not have particularly changed as a result of the exercise. But, after several decades of symbolic progress and very real sacrifices in terms of European defence and security, we can understand the need for a change in method .

Bringing politicians and experts to the table to think about the risks we face together, making sure that all can understand and make sense of their neighbours' risks, is a simple, smart and positive approach that can, to a certain extent, excise the deepest obstacle to European security and defence: the profound differences of opinion on the threats . Within this process, shared thinking on the objectives and, therefore, on the reality of what the European Union, through its members, can contribute to security and defence, has the same potential to being viewpoints together.

It is also an occasion to bring new ideas to the table on which Member States may not yet have taken a stand, somewhat increasing their chances of being adopted since it would not require backing down. Paradoxically, can bold proposals lead to a successful, inclusive Strategic Compass?

In any case, such a mechanism incidentally allows our least sensitive European partners to take better ownership of defence issues , especially since extending the exercise to resilience issues, which are broader and less military in nature, will have drawn their attention.

Finally, the logical sequence of questions, 'What threats are we exposed to? - What objectives do we set to tackle them? - Consequently, what resources are needed?', and answering them through various workshops of different sizes depending on the field and the Member States involved, encourages a constructive approach and an unprecedented sharing of viewpoints and assessments of all Europe's security problems--it is up to the EEAS to synthesise them.

We can add that France is not the initiative behind the approach, which is an advantage for an exercise intended to strengthen Europe's security and defence apparatus and removes certain suspicions. Along the same lines, during its presidency France must carefully refrain from conspicuously trying to take advantage of the compass's orientation (see below).

According to most sources, the threat assessment is of good quality and is already finished, making it a solid basis for the rest of the study . Information was shared between intelligence services without any hesitation. In particular, the universal intelligence services of France and Germany have been able to provide useful information to other Member States, most of whose intelligence services are regional in scope. But the content of this assessment would obviously be greatly diminished if, at this stage, it were to be politically adopted . 17 ( * )

Regarding the objectives, the workshops were reportedly very well attended, without a 'free rider' attitude. The 'non-paper' system works - for example, France coordinated the production of a non-paper on crisis management signed by 14 states (Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain).

The intermediate scoping paper (see above) set the bar high enough to avoid overly general, and usually sterile, discussions. The more granular the Strategic Compass is, the easier it will be to apply operationally.

Of course, Member States do not each place the same level of importance on the Strategic Compass . In this regard, embassy contributions show that this importance is often correlated to the importance they place on the CSDP and strategic autonomy.

But the overall take-up of the approach remains satisfactory, with brainstorming sessions that brought together governments, think-tanks and experts seen as generally productive, even if more space could have been given to the latter. In essence, we have only one true regret concerning the method, but it is a big one: the consultation and discussions were not extended to parliaments, depriving the Strategic Compass of a means to enrich discussions and to gain a deeper understanding among European citizens, the absence of which could weigh heavily when it comes to completing the process .

To some extent, this report aims to address this shortcoming, confirmed by all the contributions from our embassies: in the EU, the Strategic Compass is uniformly absent from public debate .

3. A 'Strategic Compass' that does not employ divisive concepts

From our point of view, it is clear that the Strategic Compass's ultimate goal is strategic autonomy for the EU, a concept that we have promoted in a report entitled "European Defence, the Challenge of Strategic Autonomy". 18 ( * ) One of the first recommendations of this report was, with a view to achieving this autonomy, ` work must be done for the collective preparation of a European White Paper on Defence, a link that is currently missing in the chain between the EU's Global Strategy, its capacity processes, and its existing operational mechanisms ', an ambition that the Strategic Compass could partially or totally fulfil.

But this concept of strategic autonomy, like that of "European sovereignty", not to mention the very French ' Europe de la défense ' - an expression that is strictly untranslatable - is bound to provoke serious reservations from States that continue to see it as a way of distancing ourselves from, or even seceding from, NATO. Translated into English, ' autonomie stratégique ' (strategic autonomy) takes on a harsher meaning 19 ( * ) that triggers a knee-jerk rejection from Member States for whom NATO's protection seems the most vital while arousing mistrust as to the intentions of those who promote it.

Let's be tactful, knowing that only the idea counts: making Europe capable of taking action, even by itself, for its security . It is this capability for action that we are trying to promote.

Since the Strategic Compass is supposed to bring all Europeans into agreement on new lines of progress for European security and defence, we should be pleased that the discussions on the Strategic Compass are organised around concrete problems , thus avoiding the misunderstandings that still arise when employing these concepts. To this end, the Strategic Compass remains inspired by a Germany whose pragmatism reassures other countries.

Similarly, this report is not structured around these concepts . This choice is all the more necessary because, having withdrawn from NATO from 1966 to 2009, having promoted the idea of a European army, and now being the only Member State to possess nuclear weapons, France cannot promote these concepts without immediately arousing the suspicion that it is trying to promote an EU defence without the United States in a De Gaullian gesture whose flame never seems to be completely extinguished.

It is true that the EUGS explicitly makes strategic autonomy an objective to be achieved , which allows France to deny ownership of the concept. And it is true that this objective found new resonance during the Trump administration among Member States worried about the weakening of the NATO umbrella. But, as we will see, the election of Joe Biden and his confirmation of the US's commitment to NATO has radically altered the situation to the extent that, now, for most Member States:

- either the expression triggers distrust, 20 ( * )

- or the expression is used without hesitation, but then stripped of its core meaning, i.e. by limiting it to resilience by targeting the economic, technological, digital (particularly from the point of view of cyberdefence), trade, health, food or environmental fields, without addressing strictly military or defence issues.

B. ... TO JUMPSTART THE CSDP21 ( * ) ...

To achieve a more effective EU security and defence policy, the EU Global Strategy (EUGS, see above) was supplemented by an Implementation Plan on Security and Defence (IPSD), which arose from the conclusions of the Council of the European Union on 14 November 2016. It established the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD), relaunched the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), established the Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC) and reinforced the EU's rapid reaction capability, which includes the European Union Battlegroups (EU BGs). The Council also adopted the European Defence Action Plan (EDAP), which includes the establishment of the European Defence Fund (EDF), and a plan to implement the EU-NATO Warsaw Declaration of 8 July 2016. These instruments were largely preceded by the establishment of the European Defence Agency (EDA) and have since been joined by the European Peace Facility (EPF).

Despite this proliferation of 'acronym' initiatives, the relaunch of the CFSP/CSDP by the Lisbon Treaty and then the EUGS has been disappointing. Cooperation on capabilities does not lead to sufficiently effective coordination to truly increase the EU's autonomy, while the CSDP is proving to be less and less active on the ground, in contrast to the intensity and frequency of crises on the EU's doorstep.

The assessment suggests untangling the web of existing instruments, which implies initially separating the CSDP's capability and operational aspects.

1. The capability aspect

Here, the aim is to allow the European Union to overcome its capability shortfalls while acquiring a "European Defence Technological and Industrial Base" (EDTIB) , which will create jobs and, above all, be essential to its autonomy in security and defence. It is worth remembering that, in the Strategic Compass, capabilities constitute the third 'basket', whose size is determined by the first two, which address crisis management and resilience objectives, respectively.

a) Overcoming inertia

The many instruments available, which are clearly not well coordinated, have produced disappointing results, with a European security and defence capability that is much lower than the level of military spending would suggest.

The fault lies in a lack of common will : Member States are ontologically driven to act autonomously in the military field, which has a strong sovereign aspect. They tend to allocate their capability investments according to their own strategic interests and their desire to maintain control in line with their idea of their own power and rank.

So, we should not be surprised that the CSDP's capability achievements are still meagre compared with those that result from national initiatives or partnership projects outside the CSDP , for example those that have united France and the United Kingdom for more than 10 years under the Lancaster House agreements, in particular the Combined Joint Expeditionary Force (CJEF), or those that unite it with Germany with major capability projects such as the FCAS (future combat air system) and the MGCS (Main Ground Combat System), the "tank of the future". 22 ( * ) Similarly, NATO elicits a significantly better coordinated capability response than that of the CSDP (see below).

Will the Strategic Compass, by building a measure of consensus on the threats, encourage some commonality of views on the capabilities deemed necessary and, therefore, greater political involvement by Member States in mobilising capability instruments, particularly with a view to establishing an EDTIB?